Volume 1: Basic TechniquesIntroduction |

In the first volume of ‘The Journalist Today News Manual’ we concentrate on the basic skills of journalism.

We start with a chapter describing in simple terms what news is, then take you step-by-step through the process of structuring and writing a news story.

In the middle chapters we give guidance on writing styles for journalism and the correct ways of presenting what you have written. We also discuss some useful books and other resources for journalists.

Finally we introduce basic reporting skills such as interviewing and reporting speeches, skills which every good journalist needs.

The first six chapters are the most important for journalists new to the profession. Spend some time on them. Read them thoroughly - several times if necessary - until you are confident that you can recognise a possible news story and then write it in a simple straightforward style. The best way to learn any skill is through practice, so take every opportunity you can to write news stories. Write and write and write again until your skills are as sharp as a razor.

Chapters 7 to 15 cover the basic techniques of researching and presenting news while Chapters 16 to 24 cover basic reporting skills, which you must practise too. They lay the foundations for most reporting tasks you are likely to encounter as a journalist.

The structure of this volume of 'The News Manual' has changed slightly from the book version. To save you having to scroll down too much text on-screen, some chapters in the book have been split into several web pages for this online edition. If you are new to 'The News Manual', you might like to read these 'linked' chapters together, e.g. Chapters 10 to 13 on Language & style. To make it easier to read these whole topics from start to finish, links have been provided at the bottom of each page to take you to the next instalment in that series.

There are two ways of finding things in The Manuals.

|

Journalist Today

What do journalists do? Journalists work in many areas of life, finding and presenting information. However, for the purposes of this manual we define journalists principally as men and women who present that information as news to the audiences of newspapers, magazines, radio or television stations or the Internet. Journalist Today and eeroju blog started february 19th 2009. Journalist Today want to give details about important journalists and media organisations to the needy persons.

Tuesday, May 1, 2012

Journalist Today News Manual-vol-1

What is news?

What is a journalist?

Chapter 2: What is a journalist? |

Here we will discuss: who journalists are and what they do; why people become journalists; and what qualities you need to be a good journalist.

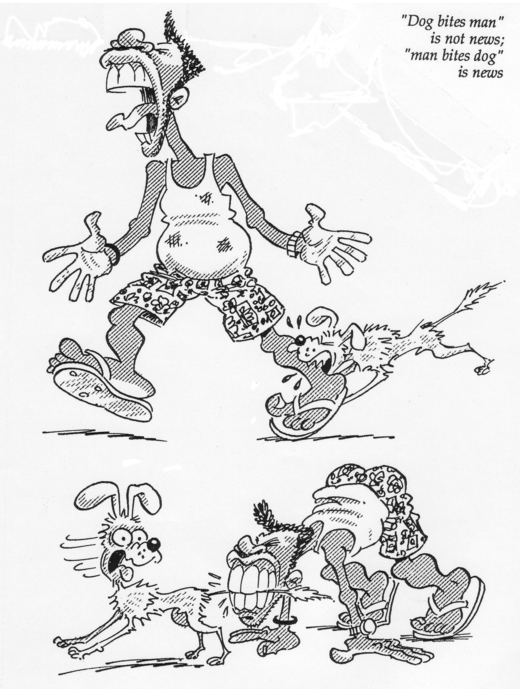

____________________________________________________________

Journalists work in many areas of life, finding and presenting information. However, for the purposes of this manual we define journalists principally as men and women who present that information as news to the audiences of newspapers, magazines, radio or television stations or the Internet. What do journalists do?Within these different media, there are specialist tasks for journalists. In large organisations, the journalists may specialise in only one task. In small organisations, each journalist may have to do many different tasks. Here are some of the jobs journalists do:Reporters gather information and present it in a written or spoken form in news stories, feature articles or documentaries. Reporters may work on the staff of news organisations, but may also work freelance, writing stories for whoever pays them. General reporters cover all sorts of news stories, but some journalists specialise in certain areas such as reporting sport, politics or agriculture. Sub-editors take the stories written by reporters and put them into a form which suits the special needs of their particular newspaper, magazine, bulletin or web page. Sub-editors do not usually gather information themselves. Their job is to concentrate on how the story can best be presented to their audience. They are often called subs. The person in charge of them is called the chief sub-editor, usually shortened to chief sub. Photojournalists use photographs to tell the news. .i.photojournalists;They either cover events with a reporter, taking photographs to illustrate the written story, or attend news events on their own, presenting both the pictures and a story or caption. The editor is usually the person who makes the final decision about what is included in the newspaper, magazine or news bulletins. He or she is responsible for all the content and all the journalists. Editors may have deputies and assistants to help them. The news editor is the person in charge of the news journalists. In small organisations, the news editor may make all the decisions about what stories to cover and who will do the work. In larger organisations, the news editor may have a deputy, often called the chief of staff, whose special job is to assign reporters to the stories selected. Feature writers work for newspapers and magazines, writing longer stories which usually give background to the news. In small organisations the reporters themselves will write feature articles. The person in charge of features is usually called thefeatures editor. Larger radio or television stations may have specialist staff producing current affairs programs - the broadcasting equivalent of the feature article. The person in charge of producing a particular current affairs program is usually called theproducer and the person in charge of all the programs in that series is called theexecutive producer or EP. Specialist writers may be employed to produce personal commentary columns or reviews of things such as books, films, art or performances. They are usually selected for their knowledge about certain subjects or their ability to write well. Again, small organisations may use general reporters for some or all of these tasks. There are many other jobs which can be done by journalists. It is a career with many opportunities. Why be a journalist?People enter journalism for a variety of reasons but, money apart, there are four main motives:The desire to writeJournalists are the major group of people in most developing countries who make their living from writing. Many young people who see themselves as future novelists choose journalism as a way of earning a living while developing their writing skills. Although writing for newspapers and writing for books require different qualities, the aspiration to be a great writer is not one to be discouraged in a would-be journalist.The desire to be knownMost people want their work to be recognised by others. This helps to give it value. Some people also want to be recognised themselves, so that they have status in the eyes of society. It is not a bad motive to wish to be famous, but this must never become your main reason for being a journalist. You will not be a good journalist if you care more for impressing your audience than for serving their needs.The desire to influence for goodKnowing the power of the printed or spoken word or image, especially in rural areas, some people enter journalism for the power it will give them to influence people. In many countries, a large number of politicians have backgrounds as journalists. It is open to question whether they are journalists who moved into politics or natural politicians who used journalism as a stepping stone.There is a strong belief that journalists control the mass media but the best journalists recognise their role as servants of the people. They are the channels through which information flows and they are the interpreters of events. This recognition, paired with the desire to influence, can produce good campaigning journalists who see themselves as watchdogs for the ordinary man or woman. They are ready to champion the cause of the underdog and expose corruption and abuses of office. This is a vital role in any democratic process and should be equally valuable and welcome in countries where a non-democratic government guides or controls the press. There is a difference between the desire to influence events for your own sake, and the desire to do it for other people. You should never use journalism for selfish ends, but you can use it to improve the life of other people - remembering that they may not always agree with you on what those improvements should be. There is a strong tradition in western societies of the media being the so-called “Fourth Estate”. Traditionally the other three estates were the church, the aristocracy and the rest of society but nowadays the idea of the four estates is often defined as government, courts, clergy and the media, with the media – the “Fourth Estate” – acting as a balance and an advocate for ordinary citizens against possible abuses from the power and authority of the other three estates. This idea of journalists defending the rights of ordinary people is a common reason for young people entering the profession. The desire for knowledgeCuriosity is a natural part of most people's characters and a vital ingredient for any journalist. Lots of young men and women enter the profession with the desire to know more about the world about them without needing to specialise in limited fields of study. Many critics accuse journalists of being shallow when in fact journalism, by its very nature, attracts people who are inquisitive about everything. Most journalists tend to know a little bit about a lot of things, rather than a lot about one subject.Knowledge has many uses. It can simply help to make you a fuller and more interesting person. It can also give you power over people, especially people who do not possess that particular knowledge. Always bear in mind that power can be used in a positive way, to improve people's lives, or in a selfish way to advance yourself. What does it take?Most young men and women accepted into the profession possess at least one of the above desires from the start. But desires alone will not make a successful journalist. You need to cultivate certain special qualities and skills.An interest in lifeYou must be interested in the world around you. You must want to find things out and share your discoveries with your readers or listeners - so you should have a broad range of interests. It will help if you already have a wide range of knowledge to build upon and are always prepared to learn something new.Love of languageYou cannot be a truly great journalist without having a deep love of language, written or spoken. You must understand the meaning and flow of words and take delight in using them. The difference between an ordinary news story and a great one is often not just the facts you include, but the way in which you tell those facts.Journalists often have an important role in developing the language of a country, especially in countries which do not have a long history of written language. This places a special responsibility on you, because you may be setting the standards of language use in your country for future generations. If you love language, you will take care of it and protect it from harm. You will not abuse grammar, you will always check spellings you are not sure of, and you will take every opportunity to develop your vocabulary. The news story - the basic building block of journalism - requires a simple, uncomplicated writing style. This need for simplicity can frustrate new journalists, even though it is often more challenging to write simply than to be wordy. Once you have mastered the basic news story format, you can venture beyond its limits and start to develop a style of your own. Do not be discouraged by a slow start. If you grow with your language you will love it all the more. An alert and ordered mindPeople trust journalists with facts, either the ones they give or the ones they receive. You must not be careless with them. All journalists must aim for accuracy. Without it you will lose trust, readers and ultimately your job.The best way of ensuring accuracy is to develop a system of ordering facts in your mind. You should always have a notebook handy to record facts and comments, but your mind is the main tool. Keep it orderly. You should also keep it alert. Never stop thinking - and use your imagination. This is not to say you should make things up: that is never permissible. But you should use your imagination to build up a mental picture of what people tell you. You must visualise the story. If you take care in structuring that picture and do not let go until it is clear, you will have ordered your facts in such a way that they can be easily retrieved when the time comes to write your story. With plenty of experience and practice, you will develop a special awareness of what makes news. Sometimes called news sense, it is the ability to recognise information which will interest your audience or which provides clues to other stories. It is also the ability to sort through a mass of facts and opinions, recognising which are most important or interesting to your audience. For example, a young reporter was sent to cover the wedding of a government minister. When he returned to the office, his chief of staff asked him for the story. "Sorry, chief," he replied. "There isn't a story - the bride never arrived." As his chief of staff quickly pointed out, when a bride does not turn up for a wedding, that is the news story. The young reporter had not thought about the relative importance of all the facts in this incident; he had no news sense. A suspicious mindPeople will give you information for all sorts of reasons, some justified, others not. You must be able to recognise occasions when people are not telling the truth. Sometimes people do it unknowingly, but you will still mislead your readers or listeners if you report them, whatever their motives. You must develop the ability to recognise when you are being given false information.If you suspect you are being given inaccurate information or being told deliberate lies, do not let the matter rest there. Ask your informant more questions so that you can either satisfy yourself that the information is accurate or reveal the information for the lie that it is. DeterminationSome people call it aggressiveness, but we prefer the word determination. It is the ability to go out, find a story and hang on to it until you are satisfied you have it in full. Be like a dog with a bone - do not let go until you have got all the meat off, even if people try to pull it out of your mouth.This means you often have to ask hard questions and risk upsetting people who do not want to co-operate. It may be painful but in the end you will gain their respect. So always be polite, however rude people may be. The rule is simple: be polite but persistent. While you are hunting for your story, you may drive it away by being too aggressive. Sometimes you may have to approach a story with caution and cunning, until you are sure you have hold of it. Then you can start to chew on it. FriendlinessYou need to be able to get on well with all sorts of people. You cannot pick and choose who to interview in the same way as you choose who to have as a friend. You must be friendly to all, even those people you dislike. You can, of course, be friendly to someone without being their friend. If you are friendly to everyone, you will also be fair with everyone.ReliabilityThis is a quality admired in any profession, but is especially valued in journalism where both your employer and your audience rely on you to do your job. If you are sent on an interview but fail to turn up you offend a number of people: the person who is waiting to be interviewed; your editor who is waiting to put the interview in his paper or program; your readers, listeners or viewers, who are robbed of news.Even if you are late for an appointment, you will upset the schedules of both your interviewee and your newsroom and risk being refused next time you want a story. In a busy news organisation, punctuality is a necessity. Without it there would be chaos. To summariseThere are many reason for becoming a journalist and many type of journalists to become. It is a career with many challenges and rewards.Journalists must: Have an interest in the world around them. |

The shape of the news story

Chapter 3: The shape of the news story | ||

Here we will introduce the concept of the inverted pyramid, which is the basic shape of the news story. We see why this is a good way to present news.

____________________________________________________________

News stories go straight to the point. In this respect, they are quite unlike other forms of written English, such as novels and short stories, committee reports, letters and theses. All these are written primarily for people with the time to consider and absorb what has been written.They also follow the usual pattern of spoken language, in which it is generally impolite to jump straight to the main point which you wish to make without first establishing contact. For example, a female student writing home may say: What she is not likely to write home is: "Dear Mum and Dad, I am pregnant."But news stories do that; that is why they are different. In the following example, you will see that the narrative form starts at the oldest part of the story, then tells what happened in the order in which it happened. The news form starts at the most newsworthy part of the story, then fills in details with the most newsworthy first and the least newsworthy last:

Top priorityNews stories are written in a way which sets out clearly what is the top priority news, what is the next most newsworthy, and so on. This makes it easier for readers and listeners to understand.In many societies, people read newspapers and web pages in a hurry. They probably do not read every word, but skim quickly through, reading headlines and intros to see which stories interest them. Some which seem at first glance to be interesting may seem less interesting after a few paragraphs, and so the reader moves on. In other societies, people may find reading a newspaper hard work. This may be because it is written in a language which is not their first language; or it may be because they are not good at reading. They, too, will look at headlines and intros to decide which stories are interesting enough to be worth the effort of reading them. In either case, the readers will generally read less than half of most stories; there are very few stories indeed of which they will read every word. Similarly, people do not listen intently to every word of a radio or television news bulletin. Unless the first sentence of each item interests them, they allow their minds to wander until they hear something that interests them. The way a news story is written therefore has to do two things:

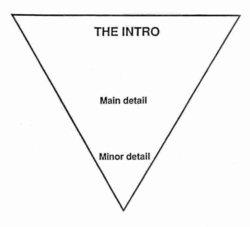

The inverted pyramidThis way of writing a news story, with the main news at the start and the rest of the detail following in decreasing order of importance, is known as the inverted pyramid. A pyramid has a broad base and tapers towards its top; the news story is just the opposite, with a broad top and tapering towards the base. It is therefore called an inverted (or upside-down) pyramid. This "shape" of the news story, with a "broad" top and a "narrow" base, is in the weight of the news itself. Look back at the earlier example, of the Hohola house fire. See how the first paragraph of the news story is the biggest news, and how the story begins to taper down towards the minor detail. This "shape" of the news story, with a "broad" top and a "narrow" base, is in the weight of the news itself. Look back at the earlier example, of the Hohola house fire. See how the first paragraph of the news story is the biggest news, and how the story begins to taper down towards the minor detail.The first paragraph, which is called theintro, contains the most newsworthy part of the story - the newest, most unusual, most interesting and most significant - told clearly and simply. This is followed by a full explanation and all the details. The most newsworthy parts of the story will be written nearest to the top of the story. The later part of the story - the tapering point of the inverted pyramid - contains detail which is helpful, but not essential. Here is an example of a short news story in the inverted pyramid; structure: This format has a practical advantage, too. If it is necessary to cut a number of lines, to fit the story into the available space on a page or into the available time in a news bulletin, it is best if the least important facts are at the end. They can then be cut without harming the story. It will be clear from this that the most important part of any news story is the intro and that intro writing is one of the most important skills of a journalist. We shall look in detail in the next chapter at how to write the intro. Advanced news writingThe simple inverted pyramid, as described here, is not suitable for all news stories. Later, in Chapter 25, we will look at some more advanced and sophisticated shapes for news stories.However, you should first master the basic inverted pyramid before moving on. TO SUMMARISE:News stories put the main point first, with other information following in order of importance, finishing with the least important.This helps readers and listeners by identifying the main news and saving them time and effort. |

Writing the intro in simple steps

Chapter 4: Writing the intro in simple steps |

Here we consider the qualities which a good intro should have. We look at how a reporter decides what information to put in the intro; and offer advice on how to make your intro more effective.

________________________________________________________

The intro is the most important part of any news story. It should be direct, simple and attention-grabbing. It should contain the most important elements of the story - but not the whole story. The details can be told later.It should arouse the interest of the reader or listener, and be short. Normally it should be one sentence of not more than 20 words for print media, and fewer for radio and television. The perfect intro

NewsworthyTo write an intro, you must first decide what makes the story news. There may be several things which are newsworthy in the story. If so, you have to decide which is the most newsworthy. This will be in the intro.In this way, your readers or listeners will be provided with the most important information straight away. Even if they stop reading or listening after the first one or two sentences, they will still have an accurate idea of what the story is about. One simple way to do this is to imagine yourself arriving back at your office and being asked by the chief of staff: "What happened?" Your quick answer to that question, in very few words, should be the basis of your intro. With some years of experience, you will find that you can recognise the most newsworthy aspect of a story almost without thinking. While you are still learning, though, it is useful to have a step-by-step technique to use. We shall explain this technique in detail later in this chapter. Short and simpleYour intro should normally be no longer than 20 words. There is no minimum length. An intro of 10 or 12 words can be very effective.Usually, an intro will be one sentence. However, two short sentences are better than one long, crowded and confused sentence. The words you use should be short and simple, and the grammar should be clear and simple. You should not try to give too much detail in the intro. The six main questions which journalists try to answer - Who? What? Where? When? Why? and How? - will all need to be answered in your news story, but they should not all be answered in your intro. Try to remember these questions as The Five Ws and H - WWWWWH. For each of those six key questions, you will need to ask whether this detail makes the story news. For example, who was drowned? A woman called Mary. Suppose it had been somebody else - would the story have been stronger, weaker or the same? Only if this detail makes the story stronger should it be in the intro. The golden rule for intro-writing is KISS - Keep It Short and Simple. Attract the readerThe intro is the most important part of the news story, because it determines whether the rest of the story will be read.If the intro is dull the reader will not want to read on. If it is too complicated the reader will give up. Your time and effort in gathering information and writing the story will all be wasted unless you write a good intro. Appropriate styleNot all possible intros are appropriate. It would be wrong to write a humorous intro for a story about a tragedy. Serious news stories call for serious intros.For example, if a man was eaten by the pet crocodile he had reared from an egg, it might seem amusing to use the saying about "biting the hand that feeds you", but it would cause great hurt to the man's family and friends for no good reason (apart from trying to show how clever you are). Simple steps in writing the introLater, we will look in detail at how you gather information for a news story. For the moment, we will concentrate on how you write your news story based on that information.You will have in front of you a notebook or a tape with a record of one or more interviews which you have conducted. You may also have information from other sources, such as handouts. Wherever your information comes from, your approach must be the same. Key pointsBefore you write anything, you have to decide what is the most newsworthy aspect of the story. To do this, let us remind ourselves of the main criteria for news:

Go through your notes, go through the handouts and, on a piece of paper, list all the key points. Now go through the list of key points, ranking them in order of newsworthiness, according to the criteria we have just mentioned. The key point which best meets the criteria will be number one on your list. Let us do this with the following example. Information

AnalysisFirst we go through the story picking out the key points. For the purposes of this exercise, we shall limit ourselves to six or seven of the most important ones.Remember our four criteria and test each of the facts against them. For example, how new, unusual or significant is it that meteorologists in Nadi detected the cyclone? After all, this is one of their jobs. Also it happened at 2 a.m. yesterday, many hours ago. More significant and certainly more up-to-date is the fact that they warned the Solomon Islands government. Maybe that is not too unusual in the event of a cyclone, but certainly an unusual occurrence in the day-to-day communication between the two nations. We will make that a key point: Now let us look for our next key point. Key point (a) is about meteorologists and government officials. We have to read on a bit further to find facts about the Solomon Islanders themselves, the people most affected by the cyclone. They were first alerted to the cyclone by radio broadcasts and police officers. They would have found this unusual and highly significant. Let us make this our next key point: Next we have mostly weather details. These should be reported in our story, but they do not themselves tell us much about the effect the cyclone is going to have on people's lives. Those people live in Honiara and we learn that 20 of their homes have been destroyed. This is quite new, unusual, significant and about people - another key point: Key point (c) tells us about "houses", now we learn the fate of the people in them. More than 100 people now have nowhere to live. That is unusual and very significant for both the people themselves and for the government. It is also as up-to-date as we can get: The next sentence gives us the real tragedy of the story - six people have been killed. This fact fills all the criteria for news. It is new, it is unusual for a number of people to die so suddenly in such circumstances and it is significant for their families, friends and the authorities. Most important, it is about people: We could leave it there, because mopping up after a cyclone is not unusual and it appears that Honiara was the worst hit. There are, however, 18 people who will bear some scars from the cyclone, so let's make them a key points: Right at the end of the information we find out how the six people died. Our readers or listeners will be interested in this, so we will make it our final key point: Notice that we have left out a number of details which our reader or listener might like to know. We can come back to them in the main body of the story. In the Chapters 6 and 7 we will show you how. For now, we have seven key points. We cannot possibly get them all in an intro so we must choose one, possibly two, which are the best combination of our news criteria. News angleIn most events journalists report on, there will be several ways of looking at the facts. A weatherman may take a detached scientific view of Cyclone Victor, an insurance assessor will focus on damage to buildings, a Solomon Islander will be interested in knowing about the dead and injured. They all look at the same event from a different angle. Journalists are trained to look at events from a certain angle - we call it the news angle.The news angle is that aspect of a story which we choose to highlight and develop. We do not do this by guesswork, but by using the four criteria for news which helped us to select our key points. The news angle is really nothing more than the most newsworthy of all our key points. With this in mind, let us now select the news angle for our intro from the key points. Keep referring back to the Information given earlier in the chapter. Key points (a) and (b) are not very new, nor are they really about people (simply meteorologists and governments). Key point (c) is about buildings, and the point is made better in (d) when we translate destroyed houses into homeless people. Key points (e), (f) and (g) are all about people. People slightly injured (f) are not as important as people killed (e). Key points (e) and (g) are about the same fact, but (e) gives the details in fewer words and is therefore preferable for an intro. We are left with a shortlist of (d), (e) and (f). Because 100 people homeless is more significant than 18 people slightly injured, let us take out (f). We can always use it later in the story to fill in details. That leaves us with (e) as the most newsworthy fact, followed by (d): Here we have our news angle, the basis for our intro, but on their own these eight words will leave our reader or listener more confused than enlightened. This is because we have told them part of what has happened, but not who, where, when, how or why. You should never try to answer all these questions in the intro, but we have to tell our audience enough to put the bald facts - six people killed, more than 100 people homeless - in context. Let us do it: Exactly who the victims were, why they died and what else happened need to be told in greater detail than we have space for in an intro. We will leave that until the Chapter 6. We do, however, have enough facts to write our intro, once we have rearranged them into grammatical English. Let us do that: The word count for this sentence is 25, which is too long. We repeat words unnecessarily, such as "people were" and "Honiara", and we should be able to find a simpler and more direct word than "passed through". Let us write it again: This is very nearly correct, but it contains a strange expression: "hit Honiara in the Solomon Islands". This sounds too much like "hit John in the face", so it may confuse our reader or listener. (How could Honiara be hit in the Solomon Islands?) We must simplify this. If we are writing this story for a Solomon Islands audience, then we can leave out "in the Solomon Islands". After all, Solomon Islanders know where Honiara is: If we are writing this story for readers or listeners in any other country, we can leave "Honiara" out of the intro. Of course, we shall include this important detail in the second or third paragraph. Our intro will look like this: Of course, not all stories are as simple to see and write as this. But by applying this step-by-step approach of identifying the key points and ranking them in order before you write, you should be able to write an intro for any story. TO SUMMARISE:The intro should be

|

Writing the intro, the golden rules

Chapter 5: Writing the intro, the golden rules | ||||||||||||||||||

In Chapter 4: Writing the Intro in simple steps you learned what qualities made a good intro, the importance of newsworthiness and of answering the questions Who? What? Where? When? Why? and How? (WWWWW & H) - but not all in the intro!. You also took the first steps in actually writing an intro from raw information to the finished short, crisp sentence based on the news angle.

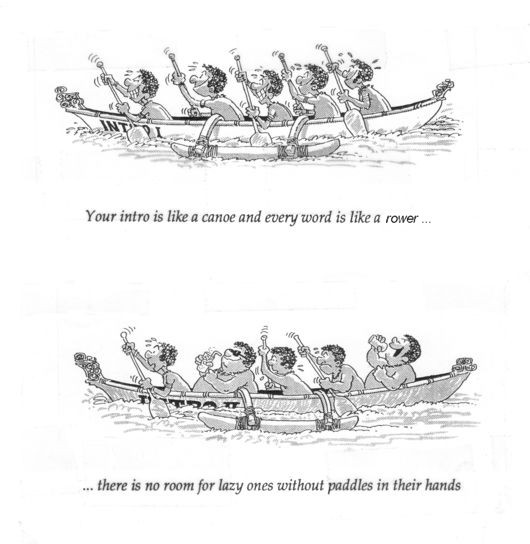

In this chapter, the second part of intro writing, we discuss some golden rules to help you write the best intro possible. KISSAs we have mentioned in Chapter 4, all news stories must answer the questions Who? What? Where? When? Why? and How? Each of these questions may have several parts, depending upon the nature and complexity of the story.Do not try to answer them all in the intro. You will only confuse your reader or listener. Stick to one or two key points per sentence, especially in the intro. Remember the golden rule is KISS - Keep It Short and Simple. You will overload your sentence and make instant understanding difficult if you include unnecessary details which can be explained more fully later in the story. Your intro is like a canoe being paddled against a fast flowing current. Every word in the sentence should be like a rower with a paddle, helping to push the sentence forward. There is no room for lazy words sitting back without paddles in their hands. They just make work harder for the rest of the words. So look closely at every word and ask yourself: "Does it have a paddle in its hand?" If it doesn't, throw it overboard! Some of the fattest and laziest words to be found in the intro canoes are titles. Inexperienced journalists often think that they have to put full titles in the intro when, in fact, they belong later in the story. Try to shorten titles for your intros wherever possible.  In the following example, you will see that a general description of the person in the intro, followed by the full name and title in the second paragraph, works much better: In the following example, you will see that a general description of the person in the intro, followed by the full name and title in the second paragraph, works much better:

Active voiceUse the active voice wherever possible. An active voice sentence uses the simple grammatical structure of subject-verb-object.The sentence "the man hit the table" is in the active voice, where the table is the object of the verb "hit". The sentence "the table was hit by the man" is in the passive voice. As you can see, the first sentence is not only shorter, but it is far simpler and easier to understand. This is especially important when your reader or listener speaks English as a second or third language. The following examples will demonstrate this rule:

The main exception to this rule is when the object of the sentence is much more newsworthy than the subject. For example:

Note that we used the passive voice in the final intro version of our cyclone story. This was because the victims - the six dead and more than 100 homeless - were more important than the cyclone itself. Remember, news is about people. We could have written it in the active voice, putting the cyclone as the subject of the sentence:

Always begin your intro with your most newsworthy key point, even though you may include another key point in the intro, in what is called a subordinate clause. You will recognise subordinate clauses as they usually begin with words like "while...", "as...", "although..." and "despite...".However, this delays the big news until the middle of the intro, instead of putting it at the very beginning. Facts FirstDon't think that, because an important person says something important, his name should come first. Let the facts come first in the intro.Remember to ask yourself: "How does this affect my readers' or listeners' lives?" The answer to that question is the heart of the news story, not the name or title of the person who made the announcement. You will see in the following example how the full name and titles in the wrong version of the intro makes it overloaded with detail, and hard to understand:

Up-to-dateKeep the story fresh. Remember that one of our four criteria for news is "Is it new?" One way in which the reader judges the newness or otherwise of a sentence is in the verb tense. Wherever possible use the present or future tense in your intro.In the following example, we focus on the real news, which is in the future - the visit of Prince Charles - rather than on the announcement, which happened last night:

In the next example, we use the present tense "is" rather than the past tense "was". Although the announcement was made last night, what was said is still true today - such things do not change overnight:

No quotesDo not begin a news story with quotes. The value of the quote is dependent entirely on the speaker. For that reason, it is important to know who is speaking before we know what is said.It really comes down to this: If someone is expressing an opinion (and most quotes are expressions of opinion), then the name of the opinion-expresser should come first, so that readers and listeners can make their own assessment of the opinion. If, on the other hand, the speaker is dealing in facts or revealing something so far unrevealed, let the facts speak first. In the following example, we can take it as a fact that income tax will rise. The Finance Minister says so, and he is the one who decides such things. (Of course, politicians do not always deliver everything they promise; but if they promise something unpleasant, you may be sure that they are not doing it to win votes, so we can believe that it is true.

In the next example, we take the content of what has been said, and present that as fact. The full quote is rather long, but we should be able to use it later in the story.

Once you have written your intro, you should read it again carefully, asking yourself the following questions:The fact that this will be the first school swimming pool on the island is not included in the quote - this is a case where journalists must set the news in context by applying their own background knowledge.

Check-list

Never be satisfied with your first attempt, however good. Always ask: "Can it be better?" TO SUMMARISE: The intro should be

|

Writing the news story in simple steps

Chapter 6: Writing the news story in simple steps |

Here we finish the job of writing the news story, which we began in Chapter 4: Writing the intro in simple steps. We consider ranking key points, structuring them in a logical way, and the importance of checking the story before handing it in.

_______________________________________________________

The first hurdle has been cleared when you have written your intro. You have made a good start - but only a start. You now have to tackle the rest of the story to ensure the second, third and following paragraphs live up to the promise of the intro.With a thorough understanding of the story, its content and its implications, and with the appropriate intro composed, the remainder of the story should fall into place quite naturally. It should become natural for you to take the readers and listeners by the hand and lead them through the story so that they absorb easily the information you have gathered. Remember the inverted pyramidRemember the inverted pyramid. Using this structure, the first sentence or first two sentences of the story make up the intro and should contain the most important points in the story. In the sentences below the intro, detail is given which supports the facts or opinions given in the intro; and the other most newsworthy details are given. Less important details and subsidiary ideas or information follow until the story finally tails away to the sort of details which help to give the full picture but which are not essential to the story.A story written as an inverted pyramid can be cut from the bottom up to fit limited space or time. Length and strengthThe actual length of the news story should not be confused with the strength of the story. Some very strong stories about major issues may be written in a few sentences, while relatively minor stories can sometimes take a lot of space. However, it is usual for stronger stories to be given in more detail. Whatever the length of the story, the bottom point of the inverted pyramid - the place where we stop writing - should be the same. That is the level at which further details fail to meet the criteria for newsworthiness.Simple steps in writing the news storyAs with writing the intro, if you follow a step-by-step approach to the rest of the story you will make your task simpler and easier. We have already chosen key points, a news angle and written an intro about Cyclone Victor. Let us now return to that information and write the full news story.The amount of detail which you include will be different for print and broadcasting. If you are writing for a newspaper, you will need to include as much relevant detail as possible. If you are writing for radio or television you will give much less detail. For example, a newspaper report should certainly include the names and other details of the dead and injured people, if those details are available. You will not want to include these details in a radio report unless they are especially noteworthy. One reason for this is that newspaper readers can jump over details which they do not want, and carry on reading at a later part of the story. Radio listeners and television viewers cannot do this, so you must make sure that you do not give details which most of your listeners will not want. If you do, you will bore them, and they may switch off. It is also true, of course, that you can fit much more news into a newspaper than into a radio or television bulletin. Radio reports have to be short so that there is room for other reports in the bulletin. InformationLet us now return to the Cyclone Victor example, which we used in the Chapter 4.This is the information you have already been given:

Key pointsThese are the seven key points from which we selected our intro:

The introBy filling in just enough of the Who? What? Where? When? Why? and How? to allow the intro to stand alone if necessary, we finally wrote the intro:

OptionsWe have three choices at this point for writing the rest of the story. We could tell it chronologically - that means in the time order in which the events happened. Or we can tell it in descending order of importance of the key points, all the way down to the least newsworthy at the end. Or we can use a combination of these two approaches, i.e. we can begin by giving the key points in descending order then fill in the less important details in chronological order.Whichever option we choose, there must be a clear logic behind the way the story is told. This will make it easy for the reader to follow and understand it. There are many ways in which you could show visitors around your village or town, some of which would be logical and some illogical. You might show them the centre of the village first, then move to the outer buildings, and finish with the river and the food gardens. Or you might show everything to do with one family line first, then move to a second family line, and so on. Visitors could follow and understand either of these. However, if you wander at random through the village, pointing out things as you happen to see them, your visitors will probably become confused. So it is with writing the news story. You must choose a clear and simple sequence for telling the facts and giving relevant opinions. In this way your readers or listeners will not become confused. To return to our Cyclone Victor example, let us choose to give the main key points in descending order of importance and then to tell the story in chronological order to give the minor details. This will demonstrate both of the other approaches. Ranking the key pointsWe have already chosen (e) and (d) for our intro. In what order should we put the other key points?Clearly the deaths need explaining if possible, as does the damage to people's homes. Because lives are more important than homes, let us take (g) as our next key point, followed by (f) which is about injuries: Notice that we split key point (g) into two halves. This was partly to stop the paragraph from being too long and partly to emphasise the unusual nature of the deaths of the three men in the car. It is less unusual for people to be killed by flying debris in the middle of a cyclone, and we filled that paragraph out a bit by including details of the injured. Now let us tell our readers or listeners more about the homeless: Notice here that we changed the word "houses" to "homes", since "homes" are houses with people living in them. We also changed the phrase "sustained considerable structural damage" to "were badly damaged". As in the intro, you must avoid overloading any sentence in your story with unnecessary words - remember the canoe. The original phrase was just jargon. The rewritten phrase is shorter and simpler to understand. Telling the rest of the storyWe have so far used five of our key points in the first four paragraphs of our news story. The remaining two key points are facts about the cyclone itself - how it was spotted and how people were warned. There are clearly lots of details which can be given here.It would be possible to write the rest of the story by choosing more key points from the information left, ranking them according to newsworthiness then writing them in order. This is, however, very complicated and may confuse your reader or listener. A much simpler alternative is to now go back to the beginning of the event and tell it in chronological order, as things happened. Before we do this, we have tell our audience that we are going to change from the key points method of news writing to the chronological method, otherwise they might think that our next paragraph is our next key point (although our readers or listeners would not use that term). The easiest way of doing that is to provide a kind of summary to the first segment of our story with the paragraph:

This sentence also tells the reader or listener that we have given the most important news. Our next paragraph tells them that we are going back to the beginning of the story:

Now we have told the story of the cyclone, at the same time bringing our audience up to date with latest developments. Checking the storyBefore we hand this story in to our chief of staff or news editor, there are two more things we have to do to make sure that it is accurate; we must check for mistakes and we must check for missing details.Inexperienced journalists are often so relieved that they have actually written a story that they forget to check it properly. You should make it a firm rule to read your story through several times before handing it in. If you should find another mistake on any reading, correct it and then, because your reading has been interrupted by the correction, you should read the whole story through again from the beginning. Keep doing this until you can read it through from beginning to end without finding any errors. Only then can you hand it in. MistakesWe have to check back through our story to make sure that we have all the facts correct, the right spellings, the correct order of events, the proper punctuation. In short, is this how you want to see the story in your newspaper or hear it read out on air?Missing detailsWe have to ask ourselves whether there are still any outstanding Who? What? Where? When? Why? or How? questions still to be answered.In our cyclone example, we do not give any specific details of who the dead and injured were, or how they were killed and hurt. Why did it take the Nadi Weather Centre an hour to alert the Solomon Islands government? What is the damage outside Honiara? What is going to happen to all the homeless people? The amount of detail which we include in the story will depend on how much we feel our readers or listeners will want. As we explained earlier, newspapers will give more details than radio or television bulletins. In particular, we shall want the names of the six people who have been killed to publish in a newspaper report; but not in a broadcast report. There is still plenty of work to do, maybe in our next story. The final versionThe final version of our cyclone story, let us say for a newspaper, is now almost ready.We check for mistakes, and are satisfied that we have made none. We then check for missing details. We have not given the names of the dead and injured, so we might phone the police and the hospital. Both places tell us that names will not be released until the families have been informed. This must be included in our story. There are no details yet of damage outside Honiara, and it may be difficult to get that information if telephone lines are down and roads flooded. This, too, should be added to the story. Our finished version should now look like this:

TO SUMMARISE:Remember to read your story through thoroughly before handing it in. If you find any errors, correct them - then read it through again.Ask yourself the following questions:

|

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)